What If You Started with Your Substitutes?

Putting the Subs in Substack.

When the International Football Association Board (IFAB), soccer’s official rule-making body, ratified a change to allow teams to make five substitutions instead of three in 2022, it was one of the biggest modifications to the Laws of the Game in decades. Originally introduced as a makeshift solution to reduce player strain during the first games back from the pandemic, the change eventually garnered “strong support from the entire football community” on its way to being adopted permanently thanks to a heightened focus on player welfare.

Yet despite the fact that we’ve effectively played five full seasons since the shift, I don’t believe it has changed tactics as much as it could have; in my eyes, most coaches consider having access to more substitutions as more of the same thing, instead of as an invitation to innovate. With only three substitutions, a supermajority of the outfield players who start will also finish the game. However, with five substitutions, only half of the outfield players who start the game will make it to the final whistle. To me, the ability to drastically change who is on the field from the start to the end of the game can make a big difference in strategy!

As a statistician and former Chief Soccer Officer who believes there are many unexplored arbitrage opportunities in soccer, I would have loved to see this change serve as an opening to run experiments that could challenge some of our fundamental assumptions about the game. One of those assumptions is that we should virtually always begin a match with our best available players. You can argue that tactical tweaks and load management sometimes override that principle in practice, but I think it’s uncontroversial to say that coaches generally want to start with their strongest lineup.

But what if you started with your substitutes? More specifically: if we think that Player X (the “starter”) is better than Player Y (the “sub”), and therefore our team will be better off if Player X plays 60 minutes while Player Y only plays 30 minutes, then how are we sure that the optimal strategy is for Player X to play the first 60 minutes rather than the last 60 minutes? I wish someone were crazy enough to put that question to the test.

An Overly Simplified Thought Experiment

To understand why a team might want to try this, assume Team A and Team B are two evenly matched teams that follow the most basic, standard model of substitutions—start with your best players and swap them out for slightly worse players 60 minutes into the game. The teams will remain evenly matched throughout the entire game because their players will get tired at the same rate, their starters will be replaced at the same time, and their subs are of the same caliber as each other, even though they are worse than the players they replace.

Now assume that Team A inverts the standard model instead—start with your “subs” and swap them out for your “starters” 30 minutes into the game. Team A would purposely put themselves at a disadvantage at first but would gain an advantage later in the game. It would look something like this:

0’–30’: Team A play a weakened lineup against Team B’s strongest lineup.

30’–60’: Team A bring on their starters. Both teams have their strongest lineups, but Team A has fresher legs.

60’–90’: Team B bring on their subs. Team A finish the game with their strongest lineup against Team B’s weakened lineup.

Would this actually result in a net advantage to Team A over the course of the entire game? I have no clue. But I’m surprised no one has tried to find out! I’m sure many innovations in the history of the game were once considered absurd.

Of course, this thought experiment is extreme for the sake of simplicity, and it doesn’t account for the flexibility needed to make tactical adjustments or injury substitutions later in the game. I don’t think burning all your subs in the first 30 minutes would be smart, but that’s precisely why the shift to five substitutions opens so many doors: a coach can make two subs in the first half and still have three subs remaining in the second half, just like they did before the IFAB rule change.

A Cross-Sport Analogy

To my knowledge, no one has attempted to do this in soccer, so it’s not possible to quantify the advantage (or disadvantage!) that would result from such a strategy. In order to illustrate how a similar approach could be analyzed mathematically, I’ll turn to college squash instead.

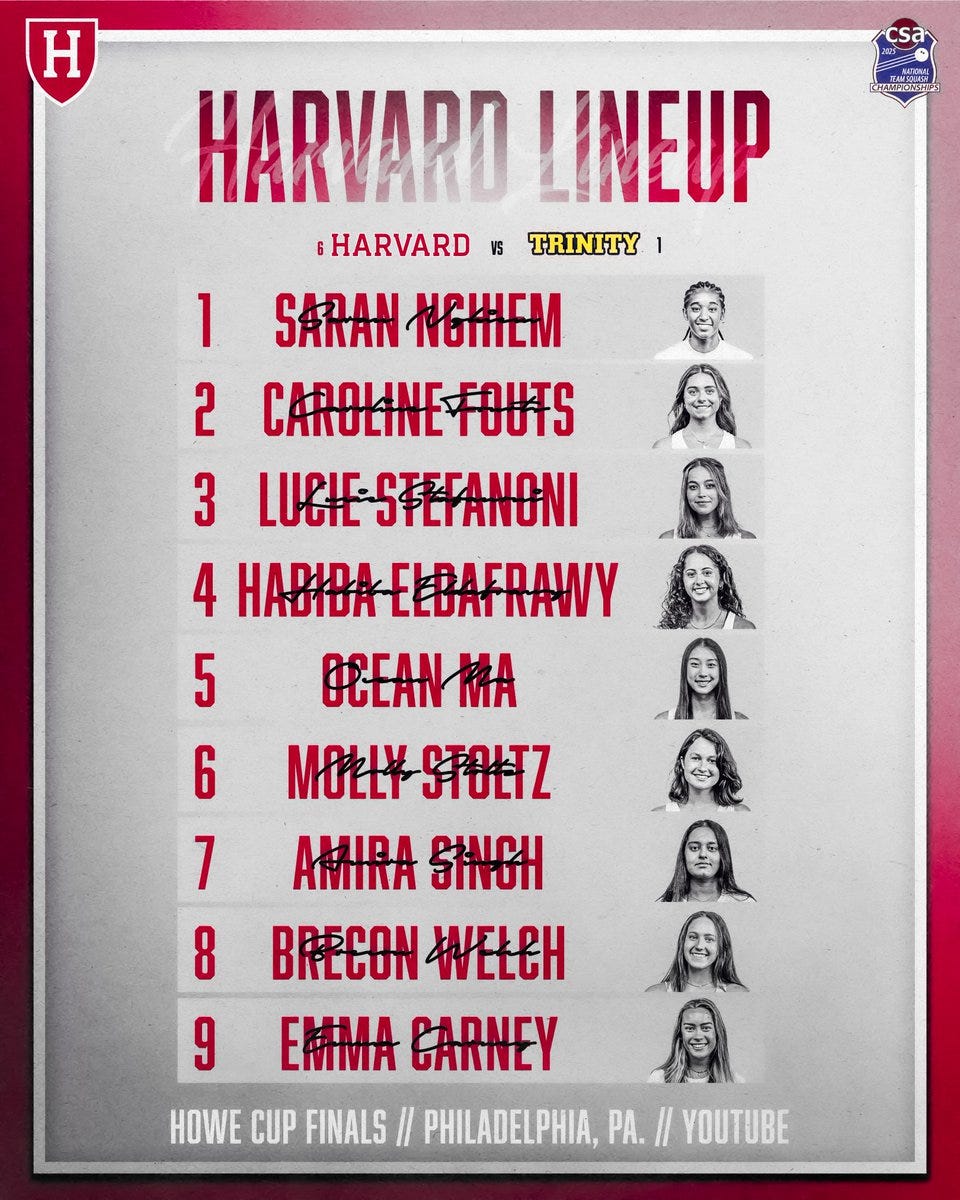

In college squash rules, when Team A plays Team B, the winner is determined in a best-of-nine series of 1v1 games; Team A’s #1 seed (A1) plays against Team B’s #1 seed (B1), A2 plays against B2, and so on.

For the sake of this thought experiment, assume that Team A and Team B are evenly matched in the sense that A1 and B1 are equally as good as each other but better than A2 and B2, who are in turn equally as good as each other but better than A3 and B3, and so on. To keep things short, I’ll only look at a best-of-five series.

When both teams start with their best players and move successively down their rankings, both teams have a 50% probability of winning each individual game, as well as a 50% probability of winning the entire series (Scenario 1). But what if lower seeds were guaranteed to beat higher seeds? In that case, Team A could “start with their substitute” and move player A5 into the first game against B1, losing on purpose. In return, however, they would have the advantage over Team B in every subsequent game, guaranteeing four wins and a victory in the series (Scenario 2).

That’s obviously not how sports work in real life, but I hope the example paints a picture of how starting with your best players is not necessarily always the optimal strategy. Other ways to calculate win probabilities as a function of seed numbers may also yield outcomes where it’s preferable to assume an early disadvantage in order to improve your overall chances of winning (Scenario 3).

The big disclaimer for the college squash analogy is that teams are not allowed to just move players up or down like this; the ranking order must be based entirely on merit, and opposing coaches can dispute lineups if they think something fishy is going on. But the fact that you’re not allowed to do it is actually good evidence that people in squash believe this could be an arbitrage opportunity!

And maybe, just maybe, it could be an arbitrage opportunity in soccer, too.

Next we’ll have two separate teams, one offense and one defence and an extra bunch of guys for dead ball situations and we’ll call it football.

That's fun to think about, Nathan! For a team sport, you'd have to overcome the mental "first goal" advantage if you're risking a greater probability of the other team scoring early. I would take more risks with my offensive line, perhaps starting with young fast less experienced players who could tire out the opponents defensive line with creative attacks that could shake up their confidence. It reminds me of baseball - I had a cousin who played for the Yankees. As a rookie, you have an early advantage at bat as the pitchers don't know how to anticipate your behavior. Over time this erodes and your at bat numbers settle into your major league range.